© Gary Carner. Copyright Protected. All rights reserved.

Here’s a snapshot of how some of my days go by when tracking down Pepper Adams data. Look at the volume of correspondence below to simply try to pin down one Byrd-Adams gig. It's kind of incredible where it eventually leads, isn't it?

On March 31, 2017 I spoke with Lisa Chaufty at the University of Utah’s Music Library regarding the Donald Byrd-Pepper Adams Quintet’s only known performance in Salt Lake City. I think I first learned about it from a Down Beat performance listing. I tried not to bias her about the actual date. Later in the day Lisa replied:

Hi there,

After searching online, it looks like the quintet was performing here from August 30-31 and September 1-4, 1960. I've been looking through digitized copies of the Salt Lake Tribune from those dates and haven't been able to find any articles or advertisements. From what I can gather, the main events advertised in the newspaper at that time included movie showings and groups like the Four Freshmen at Lagoon. Lagoon actually hosted many big names: Louis Armstrong was there the weekend before Labor Day that year.

There are no columns about local music that I've been able to find in the relevant dates that I browsed.

Sorry I can't be of more help! I would need more time to research; but I'm headed out of town this afternoon for a conference.

Best,

Lisa

I then sent the following email to Allison Connor, at a different division of the University of Utah:

Hi Allison: I'm trying to find anything--a clipping, an advertisement, a concert review--regarding the August or September appearance in SLC of the Donald Byrd/Pepper Adams Quintet. Often, it was billed as Donald Byrd's group, since he had the record contract with Blue Note. If you can find anything, I'd be very much in your debt. I'll discuss the quest to find it in my upcoming blog post (see pepperadams.com).

Thanks so much for any help you can offer,

Gary Carner

PS: More specifically, I'm showing these:

Aug 30-31: Salt Lake City: Donald Byrd-Pepper Adams Quintet gig with Duke Pearson, Laymon Jackson and Joe Dukes.

Here’s the email I received back from her:

I have started work with Ron Bitton and Lezann Keshmiri, this type of material is their area of expertise. We will let you know what progress we are making. Please let me know if you have any questions.

Thank you,

Alison

Some time later, Bitton replied:

Having looked over the Salt Lake Tribune for August 1960 and September 1-4, I’m sorry to report that I couldn’t find any press coverage or advertisements for the Donald Byrd/Pepper Adams Quintet. This isn’t unusual; aside from one brief mention of an upcoming performance by Johnny Mathis and another for the Four Freshmen, no popular music performers received any press coverage during this time period, and at the time popular music performers weren’t reviewed. Advertisements for upcoming performances were only slightly less sparse. The August and September 1960 Tribune is available on microfilm for public checkout, so you may want to double-check our search. But I regret to say this doesn’t look like a promising avenue of inquiry.

All the best,

Ron Bitton

Curator, Historical Maps and Newspapers

Marriott Library, Special Collections

Additionally, since I also reached out for a reference librarian at the Salt Lake City Public Library’s, I received this from Stephanie Goodliffe:

Mr. Carner,

I wanted to let you know that I am working on your reference request. I should be back in touch with you in the next few days.

Stephanie

A few days later, Stephanie wrote back:

We narrowed the dates of the performances by looking on Pepper Adams Chronology (https://www.pepperadams.com/Chronology/ByrdAdamsQuintet.pdf). I searched the Salt Lake Tribune for the dates surrounding the August 30-31 and September 1-4 performance dates for advertisements or reviews. I did not find any. If you would like, I can also search the Deseret News, our other local newspaper. These are the only resources that we have which would contain that type of information.

Sincerely,

Stephanie

I guess I should be happy that all these research specialists are using pepperadams.com as their source?

Hi Gary,

Thanks for your message! I took a spin through a few newspaper databases and haven’t turned up anything yet. Unfortunately, the Salt Lake Tribune isn’t indexed going back that far in our subscription newspaper databases, so I can’t run a search there. Your best bet is probably to consult the microfilm of the Tribune from the week prior and following the concerts. (I also looked in Utah Digital Newspapers to see if Salt Lake County newspapers other than the Salt Lake Tribune had covered the performance. No luck there either.)

Do you have any further information about venue(s), radio broadcasts, or other locations the quintet might have performed in during this 1960 tour? Those might give us other ways to search. I’ll keep digging, but let me know if you can share more details or if you are in a location where you can get your hands on the 1960 microfilm of the Salt Lake Tribune.

Best,

Rachel

My reply:

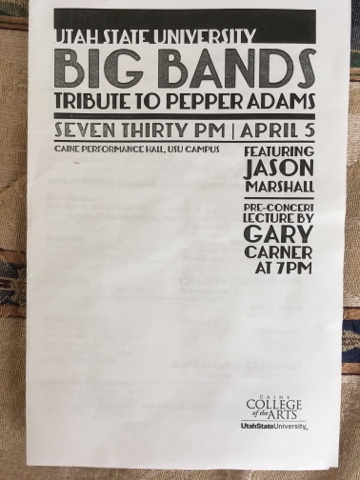

Rachel: Thanks for all your help! I'm traveling back to SLC today after a terrific visit to USU. I'll reply soon. I learned last night that Lionel Hampton played USU in either 1963 or 1964. Any info on that? February through April 1963, or January through July, 1964 seems to be the likely timeframe.

Rachel: I have this info from the Byrd-Adams tour. Not too many venues are listed herein:

Aug 2-14: Chicago: Donald Byrd-Pepper Adams Quintet gig at the Bird House, with Duke Pearson, Laymon Jackson and Lex Humphries. After Humphries unexpectedly leaves the band, Byrd replaces him with Harold Jones for the rest of the engagement, then Joe Dukes is added for the remainder of the tour.

Aug 15: Chicago: Off?

Aug 16-21: Minneapolis: Donald Byrd-Pepper Adams Quintet gig, probably at Herb's, with Duke Pearson, Laymon Jackson and Joe Dukes. Aug 22: Travel.

Aug 23-28: Dallas: Donald Byrd-Pepper Adams Quintet gig, with Duke Pearson, Laymon Jackson and Joe Dukes.

Aug 29: Travel. Aug 30-31: Salt Lake City: Donald Byrd-Pepper Adams Quintet gig with Duke Pearson, Laymon Jackson and Joe Dukes.

Sept 1-4: Salt Lake City: Donald Byrd-Pepper Adams Quintet gig. See 30-31 Aug.

Sept 5: Travel.

Sept 6-18: Denver: Donald Byrd-Pepper Adams Quintet gig, with Duke Pearson, Laymon Jackson and Joe Dukes. On the 8th, Oscar Pettiford dies in Copenhagen at age 37.

Sept 19: Travel. Sept 20-25: Detroit: Donald Byrd-Pepper Adams Quintet gig at the Minor Key, with Duke Pearson, Laymon Jackson and Joe Dukes. Adams meets Claudette Nadra, who he would marry fifteen years later. See http://instagram.com/p/rhfCQXJnmi/?modal=true.

About the Lionel Hampton query I sent Rachel, she replied:

Hi Gary,

I’m glad you had a good visit to USU! I had a chance to look into the Lionel Hampton question with some success. I started by looking through the 1963 and 1964 digitized versions of the USU Buzzer yearbook.

Here’s the 1963 Buzzer: http://digital.lib.usu.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/buzzer/id/24209/rec/56

If you look on page 50, it talks about Lionel Hampton playing Junior Prom that year (unfortunately, no pictures of him):

“The mythical land of "Misty" was the theme of the 196# Junior Prom. America's leading vibraphone player, Lionel Hampton, was featured. Kim Webb and his committee spent hard hours making this the biggest dance of the year.” To see if I could find more info, I looked at the 1963 issues of our student newspaper, the Statesman. While there is no concert or event review, there are two articles promoting prom and a pre-prom concert:

· January 30, 1963, vol. 60 no. 39, “Hamp” Concert to Precede Prom (front page)

· February 1, 1963, vol. 60 no. 40, Junior Prom Set Saturday Night (front page)

Prom was held on Saturday, Feb. 2. There’s a promotional photo of Hampton in the Feb. 1 article. Hampton give a concert in the USU Fieldhouse at 8 pm on Feb. 2 prior to prom so that students and public who weren’t attending the dance could hear him play. Admission was $1 for the public concert. Perhaps this concert was covered by the local Logan newspaper?

I also searched Hampton’s name in Utah Digital Newspapers (https://digitalnewspapers.org/) and found a few results, including this one from the Utah Daily Chronicle (the University of Utah’s student newspaper): https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/details?id=639258 Looks like he played the U’s prom on Feb. 1, 1963 (the night before USU’s). Hampton’s papers are at the University of Idaho (http://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:/80444/xv46578/op=fstyle.aspx?t=k&q=%22lionel+hampton%22#overview ) and they might contain more details.

Best,

Rachel

Then, on Apr 18, 2017 Stephanie Goodliffe wrote back:

I have checked the Deseret News from August 29-September 5, 1960, but I did not find anything that mentioned this quintet.

Sincerely,Stephanie

I wrote back: Thanks so much for checking! It looks like a dead end, at this point. Perhaps a subsequent write-up in Denver might yield something? That's for another day.

All best wishes,

Gary Carner

For those of you who want to know about the contents of the Lionel Hampton Archive, see this:

Hello Mr. Carner,

Thank you for your interest in the University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives.The papers in the Lionel Hampton Collection include business records for Lionel Hampton's record and music publishing companies, arrangements, lead sheets, and sheet music rather than specific tour or performance information. A detailed list of the contents of the collection is available here: http://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:/80444/xv46578

If I can be of further of assistance, please let me know. Thank you for your inquiury.

Darcie Riedner

Archive Assistant

Special Collections & Archives

University of Idaho Library

Such is the ebb and flow of a jazz researcher’s life! It’s what I’ve been doing for more than 33 years. Fortunately, the process led to the discovery of two new Hampton postings for the Chronology

(see http://www.pepperadams.com/Chronology/Journeyman.pdf ). They will be posted soon. Many thanks to all the Utah and Idaho librarians for their extraordinary help!