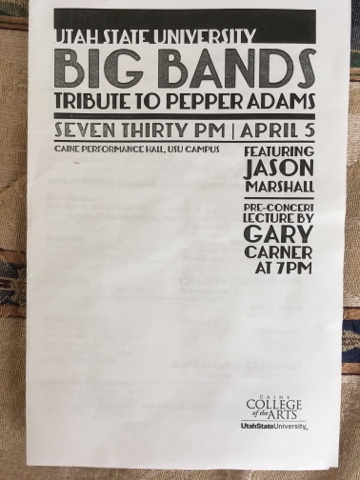

Here’s my original draft for liner notes to Pepper Adams

with the Tommy Banks Trio: Live at Room at the Top,

Reel to Reel’s forthcoming release.

That cat was something else on that horn!

–COLEMAN HAWKINS

Judging from the many accolades that he received from his

colleagues before and after his death, Pepper Adams was

equally esteemed by his elders, contemporaries, and younger

musicians. Among the old guard, Coleman Hawkins was one

of his biggest fans. “Hawkins admired Pepper,” said drummer

Eddie Locke. “He said, ‘That cat is something else on that

horn!’ . . . He didn’t say that about many people; he didn’t talk

about many guys.” According to Gunnar Windahl, Adams’s

close friend, Don Byas also adored Adams’s playing, and Milt

Hinton, out of respect for Pepper’s intellect, dubbed him “The

Master.” About Adams, Dizzy Gillespie once rhetorically asked

David Amram, “Man, that guy’s phenomenal, isn’t he?” And

backstage at a 1985 Adams benefit in New York City, Gillespie

told Cecil Bridgewater how much he admired what Pepper had

done harmonically with the instrument; how he had utilized the

baritone sax in a completely different way from other baritone

players. “His playing was unbelievable,” agreed Clark Terry,

“just fantastic! I never heard him jump into anything that

stymied him: any tune, any tempo, any key. He was a

phenomenal musician, one that could do anything. His

rhythmic sense wassuperb, his melodic sense was fantastic.

He was just a marvelous person and a marvelous musician.”

Adams’s contemporaries were just as effusive in their praise.

“He is one of my heroes,” said Bill Perkins. He’s one of the

true giants of jazz. He stood out in that rare group of jazz

soloists, the great giants of all time, people like Bird and Prez

—and John Coltrane has become that. I think Pepper was that

on his instrument—and Diz. They’re in an area where very

few have done the creative work that they’ve done. Nobody

is equal: There are some great young players around and they

owe a great debt to him, but Pepper was monolithic in his

playing. Bob Cranshaw concurred with Perkins. “Everyone

knew he was a superstar,” declared Cranshaw. “The rest of

the baritone saxophonists: They know! . . . In my book he’s

the Number One baritone saxophonist. I don’t even think of

anybody else.” Phil Woods heartily agreed: “Any baritone

player that’s around today,” he avowed in 1988, “knows that

he was Number One. It’s that simple. He was the best we

had.” Both Curtis Fuller and Don Friedman felt similarly:

“He was the greatest who ever played the baritone saxo-

phone,” proclaimed Fuller. Pepper, asserted Friedman,

“should be considered the number-one-of-all-time baritone

player. Nobody ever played as many years at that level that I

ever heard. There’s no question about it.”

According to Horace Silver, Adams “was an excellent jazz

soloist. He could handle any of the chord changes that you’d

throw up in front of him. That’s the mark of a true, great impro-

viser. In my opinion, this is why any of the great jazz soloists

get their reputation; because they’re consistent.” Bill Watrous

said about Adams, “Every time he played it was an adventure.

His ideas and his conception of the stuff that he was trying to

play was totally original.” Bassist Nabi Totah confessed, “I just

idolized Pepper. Every chorus, you’d think he’d be getting tired,

he’d play stronger than the one before. There seemed to be no

end to his ideas. He just forged ahead swinging.” Adams “gave

a personality to the baritone sax,” attested trumpeter Denny

Christianson, “that nobody else ever even came close to. No-

body could do what he did on his instrument. He could handle a

melody just like a great singer, but his improvisation was brilliant

and he had blinding speed.” Pepper, asserted Junior Cook, “was a

virtuoso, without a doubt. He exemplified all the best things that

any musician – jazz or otherwise–should aspire to: He had great

tone, he had great time, and he had great taste.”

For the younger generation, Adams was a paragon of individuality.

“There’s very few stylists, real heavyweights,” bassist Todd

Coolman once told drummer Ron Marabuto about Pepper.

“Maybe five of them. They’re really rare. He’s one of them.”

Adams was “a true master of his craft,” said Bennie Maupin, “and

absolutely one of the finest musicians of his generation.”

Saxophonist Kirk MacDonald agreed: “He really owned the music

on a very high level.” As bassist Andy McCloud pointed out,

Pepper “recorded with all the cats. He was an unknown genius. He

was like Dexter [Gordon] and one of them.” Guitarist Peter Leitch

said, “When I started to play, I realized that here’s a white person

who really played this music authentically and was still able to be

himself.” And Gary Smulyan acknowledged that Pepper “inspired

me to make a life-long study of the instrument”: It kind of made

me realize why I got into music. It was not to be a doubler. It was

not to play all these instruments and get a Broadway show. It

was to try to find a voice, and to express your life through an

instrument. That was it. Pepper was the inspiration for that.

* * *

It was Pepper’s blistering, spellbinding solo on “Three and

One” from this date that reminded me of Coleman Hawkins’s

comment and made me think of including the above excerpt

from my forthcoming Adams biography. You see, musicians

have always sung Adams’s praises, yet even to this day he’s

mostly overlooked, even by jazz historians, as one the great

postwar virtuosos. Just check the index of any jazz history

and you’ll see what I mean. Fortunately, with his extraordi-

nary playing on this marvelous release, Adams’s place among

the greatest of all jazz soloists should finally be irrefutable.

And it’s no surprise at all that it took Cory Weeds, a working

musician, to recognize this radio broadcast’s intrinsic value.

Besides revealing Adams’s brilliance as a soloist, this perfor-

mance is a vitally important document because virtually

nothing exists of his small-group work from this period. Be-

tween Encounter (Prestige, 1968), his terrific solo date with

Zoot Sims, Tommy Flanagan, Ron Carter, and Elvin Jones,

and Ephemera (Spotlite, 1973), his equally superb quartet

session with Roland Hanna, George Mraz, and Mel Lewis,

there’s barely a handful of recordings in which Pepper takes

a solo. Furthermore, just a few obscure Adams audience re-

cordings exist from this five-year span that only a few col-

lectors have heard. What I found especially fascinating was

hearing both “Patrice” and “Civilization and Its Discontents,”

two very special Adams originals, performed a full year

before he recorded them for Spotlite. This indicates that even

at this stage of his career, five years before he left the Thad

Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra to go out on his own as a “single,”

he was composing new tunes not solely for record dates, as I

previously believed. “Patrice,” it turns out, was registered at

the Library of Congress on October 29, 1970, but might this

be the world premiere of “Civ?” For this show, Adams’s select-

ion of tunes was highly representative of what he often chose to

play. With a competent band, he usually selected a few originals,

a few Thad Jones tunes, a standard or two, and he’d customarily

close his sets with “’Tis.” He especially liked old show tunes,

such as “Time on My Hands” (1930). “Stella by Starlight, of

course, was by 1972 a very well-known standard. “’Tis” was

Thad’s brief, uptempo out-theme that since 1954 Pepper almost

always utilized. “Oleo” served a similar function, though typical-

ly to both conclude a concert and stretch out a bit. And “Three

and One?” One of Thad Jones’s great compositions, it was an

Adams feature while he was a member of Jones/Lewis, and a

tune that he often called in small-group settings. Adams was a

musician who lived to play, yet whose lust for life was eroded

by his long-simmering disappointment at being defined by pro-

moters as a big-band baritonist not available for hire, ignored as

a true innovator for much of his career, and barely recorded as a

leader for most of the 1960s and ’70s. Part of his uniqueness

was due to his pedigree as a “jazz man.” As Eddie Locke explain-

ed it to me during my 1988 interview with him, “A real jazz man

will play his instrument no matter what”: He’s gonna play. He’s

not gonna make an excuse for not playing by saying, “Something

is going wrong, I can’t play.” If you love it so much, it doesn’t

make any difference. No dollars, bad musicians, good musicians,

mediocre musicians: You’re gonna blow! Pepper just happened to

also be a great player. But he was a real jazz man. . . . A real jazz

man is rare. That’s a lifestyle. That’s not just going to school. And

that’s what Pepper was about. In Detroit, you played in the joints:

slop jobs in those old, funky places. That’s a jazz man. He wasn’t

trying to play in Carnegie Hall every night. He was just going to

play some music because he loved to play. . . . People wanted to

play with him because he was a jazz man. . . . I don’t care who he

was playing with; he’s gonna sound good because he’s gonna

blow! He doesn’t give a shit about the other cats. If they play the

wrong change, he’ll play the wrong one. That’s a true jazz musician.

Bird was like that. Coleman Hawkins was like that. I put him in

some heavy company there but that’s what I’m talking about.

Enjoy!

Gary Carner Author of Pepper Adams’ Joy Road and Reflectory:

The Life and Music of Pepper Adams