© Gary Carner. Copyright Protected. All rights reserved.

On March 3-5, 1944 thirteen year old Park Adams skipped school three nights in a row to attend Duke Ellington's entire run at the Temple Theatre in Rochester, New York. Adams was already playing piano, saxophone, clarinet and enjoying jazz programs on the radio. Starting in 1936, six-year-old Adams listened to Fats Waller's daily 15-minute afternoon radio show. In 1938 Adams tuned in to John Kirby's program featuring his sextet. And in 1940 he caught Fletcher Henderson's late night broadcasts originating from Nashville.

Though Adams' parents didn't play musical instruments, they owned a piano and a broad selection of 78 rpm records. Because of that, Adams was exposed very early to both jazz and classical music. By seventeen he was familiar enough with the history of the classical repertoire to get hired in the Classical Music Record Department of Grinnell's in downtown Detroit.

Adams was especially drawn to the symphonic music of his era and at a young age developed a taste for dissonant harmonies. Although Adams was still playing in the New Orleans style, his taste in music was already very well developed in 1944. One can imagine how excited Adams must have been to hear the Duke Ellington Orchestra in a concert settting.

Adams was especially drawn to the symphonic music of his era and at a young age developed a taste for dissonant harmonies. Although Adams was still playing in the New Orleans style, his taste in music was already very well developed in 1944. One can imagine how excited Adams must have been to hear the Duke Ellington Orchestra in a concert settting.

The Temple is a movie palace built in 1909 at 35 Clinton Avenue South in downtown Rochester. On the third and final evening of the Temple engagement, Ellington trumpeter Rex Stewart was curious about the enthusiastic, short-haired white kid with horn-rimmed glasses he noticed sitting by himself each night in the balcony. Intrigued, Stewart made his way upstairs, introduced himself, then brought a no doubt exasperated Adams backstage to meet Ellington's illustrious musicians, including Johnny Hodges and Harry Carney. While there Adams overheard Frederick Delius recordings being played by Ellington that commentators have reported Duke was listening to at that time.

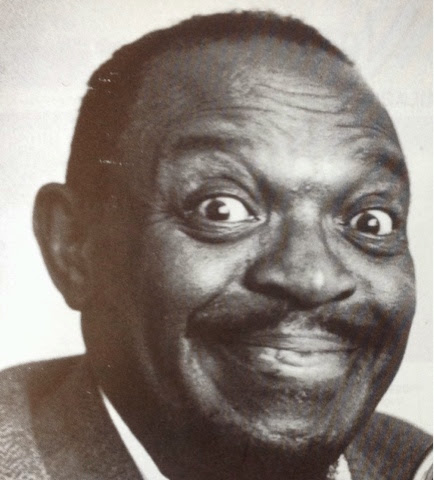

(Photo by Valerie Wilmer c. 1966)

It's hard to overstate how valuable this encounter was for Adams, or the role Rex Stewart assumed as a lifelong father figure and influential elder. Should we assume Stewart sought out young Park Adams because he was sitting by himself or presumably an anomaly in a mostly black audience? While maybe part of the equation, I believe Stewart was honoring this provocative teenager, who at the time must have been from Stewart's perspective a very special young man for going out of his way to scrape together enough money to attend the Ellington orchestra each night. Stewart was also continuing the important tradition of an elder musician supporting a young aspiring one, something that (to its detriment, I think) has mostly died off in jazz.

Consider for a moment the context. Just a few years earlier, Adams' father had died at the age of 44. Adams, an only child, was already a survivor of the Great Depression like so many who were born after 1929. His father's death, when Adams was nine, only intensified the ordeal.

The Depression had destroyed Adams' parents' way of life. It robbed them of their Detroit home and separated them for nearly four years while his father traveled throughout the U.S., looking for any work he could find. Worn down by the strain of scratching out a living, his father suffered his first heart attack in 1934 in Rome, New York, partly from the excitement of his family finally being reunified. In theory, it was intended to be a time of great joy. Instead, Adams' father lived out the remainder of his life a frail and unfulfilled man.

The Depression had destroyed Adams' parents' way of life. It robbed them of their Detroit home and separated them for nearly four years while his father traveled throughout the U.S., looking for any work he could find. Worn down by the strain of scratching out a living, his father suffered his first heart attack in 1934 in Rome, New York, partly from the excitement of his family finally being reunified. In theory, it was intended to be a time of great joy. Instead, Adams' father lived out the remainder of his life a frail and unfulfilled man.

At the Temple Theatre, Rex Stewart's profound act of kindness--his mentoring of Pepper and adopting the role of a father figure--must have filled a void in Pepper's life. It was certainly the most transcendent event of his boyhood. Very soon after meeting Stewart, Adams took a few tenor sax lessons with Skippy Williams, the tenor saxophonist in Ellington's band that Stewart introduced Pepper to backstage. Williams was the saxophonist who first replaced Ben Webster, prior to Al Sears. (I interviewed Williams, by the way, and hope to share that with you in a later post.)

That night at the Temple put in motion Adams' lifelong love affair with Ellington and Strayhorn. (Listen to Pepper's original ballads, such as "I Carry Your Heart," and you'll hear Pepper's profound debt:

http://www.pepperadams.com/Compositions/compList/ICarryYourHeart/index.html#anchor)

Pepper's close friend Gunnar Windahl told me the following about Pepper:

http://www.pepperadams.com/Compositions/compList/ICarryYourHeart/index.html#anchor)

Pepper's close friend Gunnar Windahl told me the following about Pepper:

"Every day, I think, he listened to Duke Ellington. Duke Ellington meant a lot to Pepper. I remember we were in Gothenburg. After a gig there we came into my room. I had a half a bottle of whisky and we sat talking. With my blue eyes, and as an overreacting person before such a star as Pepper Adams, I managed, 'Who is the best musician in the world, Pepper? Who do you consider the most interesting and underrated?' He said the most interesting and underrated musician in this business is Rex Stewart.' I was a bit taken aback. Then Pepper said that he seen Rex just before he died and that Rex was very disappointed that he wasn’t more recognized. I think Pepper identified with Rex’s destiny."

Pepper's life mirrored Rex Stewart's. Rex had success in the mid-1930s and '40s as one of Ellington's great soloists, then languished. Adams, according to bassist Percy Heath, was a sensation in New York when he first arrived in early 1956, created a similar stir in California in early 1957, had an influential quintet with Donald Byrd from 1958-1961, then languished. I don't mean "languished" as a pejorative term related to their musical growth or achievements but simply as a term for how much they struggled financially and how little attention they received from record companies and the international press.

Pepper, for obvious reasons, identified with struggling artists, whether it be Rex Stewart, the painter Lyonel Feininger or the composer Arthur Honegger. For Adams they were all very special because, like himself, they were unique, accomplished, had struggled financially throughout their careers and were overlooked.

Other than his very close bond with Stewart, what is it about Stewart's playing in particular that Pepper Adams admired? His off-the-wall humor, for one thing, with oblique phrases coming seemingly (as Pepper put) "out of left field." You can grasp Stewart's almost wacky sense of humor in his most well-known Ellington feature Boy Meets Horn:

Stewart was technically brilliant and harmonically adventurous. Listen and watch these three clips:

1. Duke Ellington's 1938 Braggin' in Brass: http://youtu.be/M_bFnaiyAZM

2. Nick Travis and Rex Stewart perform "There'll Never Be Another You" (1958) from the TV show Art Ford's Jazz Party: http://youtu.be/mzsJUbKwIN8

3. Also, from the legendary 1957 CBS TV show "The Sound of Jazz" Rex takes his solo on "Wild Man Blues" just after the 8-minute mark. It's replete with numerous musical paraphrases. Perhaps that's another Rex Stewart influence on Pepper? Rex's irrepressible joy is obvious throughout, especially when he openly laughs after his first four-bar statement: http://youtu.be/vo7qiXkTu4s

Also, check out Stewart's book Jazz Masters of the 30s. It's a collection of his writings that were collected posthumously. Like Pepper, Rex Stewart was very literate:

Pepper Adams was always very guarded with his emotions. According to his widow, Claudette, Pepper used music to get his emotions out and was not one to readily share the intimacies of his feelings with anyone. But Rex Stewart's death in 1967 was too much for him to contain. According to Montreal radio host Len Dobbin, Pepper broke down and wept when Dobbin told him that Stewart had died.