© Gary Carner. Copyright Protected. All rights reserved.

My apologies to any readers who expected a post yesterday and were disappointed not to see it. For more than a year I've dutifully posted every Saturday. This weekend, however, I needed a slight reprieve. Better to supply something of value than rotely produce drivel just for the sake of a deadline?

I was very pleased this past week to hear from Pug Horton, Bob Wilber's wife. Here's what she wrote:

"Sorry to have taken so long to get back to you--we have been on the road. Are you in NY? We will be coming to NY Sept 26th. Hopefully seeing Mike [Steinman] around that time too. Let me know how we can get together & Bob would love to talk about his relationship with Pepper. He talks about the time in Rochester quite a lot…He hated it except for the time he spent with him!!!"

My reply:

"Thanks so much for your email. I left NYC in 2004 and currently live in Atlanta. I'd be thrilled to speak with Bob again, either by phone or Skype, at that time. I'm heading out of town on Sept. 27th to celebrate my 30th anniversary, back on the 30th, but I'm sure I can grab an hour if those days are best for him. Just let me know.

Did you see my blog post?:

Thanks,

Gary Carner

In 1987 I interviewed Bob Wilber about Pepper Adams. It's the only time we ever spoke. There's much I'd still like to ask him about his brief time in Rochester and about his subsequent work with Pepper. As I've written, I believe that Wilber was the single most important influence on Pepper as a young player. I only came to that conclusion by virtue of my research this summer into Pepper's early life. I've had a chance to listen to many hours of interview I conducted in the late 1980s with some of the musicians who were on the Rochester scene in the mid-1940s and knew Pepper--most importantly Raymond Murphy, John Huggler, Everett Gates, Skippy Williams, Ralph Dickinson, and, of course, Bob Wilber. I'd like to ask Wilber if he remembers any specific advice he gave Pepper, such as exercises, fingerings, pieces to play, or any kind of technical advice on getting around the horn. Besides that, anything new he can tell me about Pepper as a 14- to 16-year-old would be fascinating! Wilber, much like Raymond Murphy and John Huggler, was almost three years older than Pepper. In a way, all three of them functioned as Pepper's big brothers and, to some degree, as a prosthetic family after the death of Pepper's father in 1940, when Pepper was nine. I'd like to ask Wilber about that too, or at least his perception of Pepper's sense of loneliness.

Regarding Bob Wilber and the very strong bond that he and Pepper established in those formative early days, it's not surprising how their paths continued to cross as both became in-demand professionals. I've already written how the two of them spent a good amount of time together during Wilber's one semester at the Eastman School in the Fall of 1945. Here's a summary of their very early experience, from pepperadams.com:

1945

cAug: New York: Adams and his mother travel to New York and meet Bob Wilber at a Max Kaminsky gig at the Pied Piper in Greenwich Village. The Pied Piper was later renamed the Cafe Bohemia.

Sept: Rochester NY: Adams begins 10th Grade at John Marshall High School and plays in the school band throughout the year. See

http://instagram.com/p/tyuB3PJntF/?modal=true. On Saturday afternoons, Adams, John Huggler and Bob Wilber have sessions at Bob Wilber's apartment, playing along with jazz records. See cJuly 1944. (Wilber was attending Eastman, but only that Fall semester.) Wilber goes to Adams' place to play along with jazz records and have dinner. Wilber also visits with Adams and Huggler at Raymond Murphy's house.

Oct: Rochester NY: Adams in 10th Grade. On Saturday afternoons, Adams, John Huggler and Bob Wilber have sessions at Bob Wilber's apartment, playing along with jazz records. See cJuly 1944. (Wilber was attending Eastman, but only that Fall semester.) Wilber goes to Adams' place to play along with jazz records and have dinner. Wilber also visits with Adams and Huggler at Raymond Murphy's house.

Nov: Rochester NY: Adams in 10th Grade. On Saturday afternoons, Adams, John Huggler and Bob Wilber have sessions at Bob Wilber's apartment, playing along with jazz records. See cJuly 1944. (Wilber was attending Eastman, but only that Fall semester.) Wilber goes to Adams' place to play along with jazz records and have dinner. See cJuly 1944. Wilber also visits with Adams and Huggler at Raymond Murphy's house.

Nov 29-30: Rochester NY: A serious snow storm paralyzes the city. Adams is likely homebound.

Dec: Rochester NY: Adams in 10th Grade. On Saturday afternoons, Adams, John Huggler and Bob Wilber have sessions at Bob Wilber's apartment, playing along with jazz records. See cJuly 1944. (Wilber was attending Eastman, but only that Fall semester.) Wilber goes to Adams' place to play along with jazz records and have dinner. See cJuly 1944. Wilber also visits with Adams and Huggler at Raymond Murphy's house.

I'd especially like to know if Wilber studied or hung out with Eastman professor and clarinetist Jack End. End, against tremendous institutional bias, fought to have jazz at least played by students at Eastman in the 1940s and early '50s, though at that time it was not accepted as an official part of the curriculum. Wilber, it's clear, hated his time at Eastman. Might have an association with End at least made it marginally palatable? Did Wilber introduce Pepper to End? I'd love to know more about what End dealt with at Eastman and more about End and his playing on the Rochester scene.

Unless Pepper saw Wilber in New York on a visit south to the big city, Pepper may not have seen Wilber again from January, 1946, when Wilber left Eastman, until Pepper moved to Detroit in June, 1947. That's because, much to Pepper's mother's credit, on their way west to Detroit, Pepper and his mother lived at the Hotel Edison in Manhattan for a full month. It was then that Adams and Wilber reunited. By then, Wilber was living with Sidney Bechet. Talk about getting close to the source! As musicians, Adams, Murphy and Huggler, with Wilber, had strived, in their listening and practicing, to get as close as possible to the true source of New Orleans music--"from the horse's mouth," as Huggler told me. Now, Adams could finally meet Bechet and see that Wilber was indeed living the dream. Here's my citation about that time:

1947

July: New Yor: Adams moves with his mother to New York City for a month while their belongings are transported to Detroit. They live at the Hotel Edison on 47th Street in the Theater District before moving to Detroit. Cleo Adams decided to relocate because elementary school teaching jobs paid far more in Detroit than in Rochester. Pepper meets Sidney Bechet, probably through Bob Wilber. Pepper studies saxophone with Skippy Williams, the tenor saxophonist in Ellington’s band who he met at the Temple Theatre in early March, 1944 and who first replaced Ben Webster in Ellington's band. See 3-5 Mar 1944. Adams attends rehearsals of the Joan Lee Big Band (based in Hershey PA) at Williams' apartment on 48th Street. Lee's band was an all-white, all-female group that Williams was rehearsing.

After Pepper moved to Detroit, it's not known if Wilber and Adams saw each other or remained in contact until Pepper moved to New York City in early 1956. I'd like to ask Bob about that, if they didn't speak at all for ten years, and whether Bob attended any of those heady loft-jam-sessions around New York City that were taking place when Pepper first arrived.

The first band that Adams and Wilber actually worked together in as professional musicians was Benny Goodman's. The two of them had this tour:

1959

Apr 6-9: New York: Benny Goodman rehearsals.

Apr 10: New York: Benny Goodman rehearsal. Later, Benny Goodman "Swing Into Spring" telecast.

Apr 11-21: New York: Benny Goodman rehearsals.

cApr 22: Troy NY: Benny Goodman Orchestra begins its three-week tour. The band boards a bus that morning (in front of the Hotel President on West 48 Street in New York) for its Troy gig that evening, then stays in Albany.

cApr 23: Rutland VT: Benny Goodman Orchestra's second gig of the tour.

Apr 24: Hershey PA: Gig with Benny Goodman, probably at Hershey Park. Herb Geller and Pepper Adams are featured, with the rhythm section (Russ Freeman, Turk Van Lake, Scott LaFaro, Roy Burns), on Bernie's Tune. Other band members are Taft Jordan and Bob Wilber. Dakota Staton and the Ahmad Jamal Trio are also on this General Artists tour package.

Apr 25: Off/travel?

Apr 26: Montreal: Gig with Benny Goodman at the Forum, then Adams and Herb Geller sit in after hours at the Little Vienna with trumpeter Herbie Spanier.

Apr 27: Montreal: Off day for Goodman tour. Adams does small group gig at Vieux Moulin with Herb Geller, Scott LaFaro and Roy Burns.

Apr 28: Toronto: Gig with Benny Goodman at Maple Leaf Gardens.

Apr 29: Buffalo: Gig with Benny Goodman at Kleinhans Music Hall.

cApr 30: New York: Gig with Benny Goodman at Madison Square Garden.

May: Indianapolis: Adams, Scott LaFaro and Bob Wilber sit in with Wes, Buddy and Monk Montgomery at the Missile Club.

May: Dallas: Adams rooms with Taft Jordan and shares an elevator ride in their hotel with Lassie, the celebrity TV collie, who was in town on a promotional tour.

May: Iowa City IA: Gig with Benny Goodman at the University of Iowa.

cMay 13: Pittsburgh: Gig with Benny Goodman at the Old Mosque.

cMay 14: New York: Returns from Goodman tour.

After the Goodman tour, I don't know to what degree they saw each other in New York or even worked together. There is this gig for the Duke Ellington Society, then the very fine Bobby Hackett date Creole Cooking, for which Wilber wrote the arrangements:

1966

May 22: New York: Bob Wilber gig for the Duke Ellington Society gig at the Barbizon Plaza Theatre, with Shorty Baker, Quentin Jackson, Jackie Byard, Wendell Marshall, Dave Bailey and Flo Handy. See http://instagram.com/p/sA3ydoJnrT/?modal=true.

1967

Jan 30: New York: Bobby Hackett date for MGM, with Bob Wilber, Bob Brookmeyer, Jerry Dodgion, Zoot Sims, et al. Later, possible double appearance with the Joe Henderson All-Star Big Band and Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra at the Synanon Jazz Benefit at the Village Theater preceding the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra at the Village Vanguard.

Mar 13: New York: Bobby Hackett date for MGM, with Bob Willber, Bob Brookmeyer, Jerry Dodgion, Zoot Sims, et al. Later, Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra at the Village Vanguard.

Mar 30: New York: Bobby Hackett date for MGM, with Bob Wilber, Bob Brookmeyer, Jerry Dodgion, Zoot Sims, et al. Later, Elvin Jones gig at the Five Spot. See 28-29 Mar.

After the Hackett date, I'm not sure if Adams and Wilber recorded or worked any gigs until the interesting 1972 project below for Music Minus One. The label's concept was to provide a backing band for the practicing soloist, well before Jamey Aebersold started his series. Wilber did tell me about his writing for saxophone quartet (two altos, tenor and baritone). Wilber held rehearsals at his New York City apartment, possibly in the late 1960s. Other than Wilber and Adams, someone I forget played tenor and possibly Rudy Powell played the other alto part. I don't know precisely when the rehearsals took place, if any were recorded, nor over how long a stretch of time the rehearsals lasted.

1972

June 8: New York: Bob Wilber rehearsal, probably for 19 June.

June 15: New York: Bob Wilber rehearsal, probably for 19 June. See 8 June.

June 19: New York: Bob Wilber date for Music Minus One. Later, possible Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra gig at the Village Vanguard.

In 1974, Wilber put together a band to play Ellington tunes:

1974

Apr 26: New York: Bob Wilber gig at Carnegie Hall, with Taft Jordan and Quentin Jackson, perform a tribute to Duke Ellington.

Apr 28: New York: Bob Wilber gig at the New York Jazz Museum, with Quentin Jackson, Taft Jordan, Larry Ridley and Bobby Rosengarden.

In 1977 Adams and Wilber were in a band together, led by Dick Hyman, doing a tribute to Duke Ellington:

1977

July 17: Nice: Dick Hyman gig at La Grande Parade du Jazz, broadcast on FR3 television. Also, Thad Jones sextet gig at La Grande Parade du Jazz. Later, a third festival gig: Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra at La Grande Parade du Jazz.

The Hyman gig for me has special significance. It gives me a chance to hear Pepper with the Ellington big band repertoire and imagine what it might have been like had he actually subbed for Harry Carney. I've written before that Pepper was Carney's designated sub in the Ellington band. Yet, in fifty years Carney never missed a gig! Well, I slightly exaggerate: He missed one two-week stretch of work--just once! Pepper told me that it was easier to reconstitute the Ellington reed section and slide Russell Procope or someone else from the section into the bari chair, then hire a local sub for tenor or alto, than to get Pepper to the gig.

The Hyman performance has additional significance. There's two especially wonderful Adams/Wilber moments. On the very first tune, Ellington's original theme "St. Louis Toodle-Oo," Pepper takes the first solo--classic, harmonically inventive Pepper all the way--and Eddie Daniels and Bob Wilber are both visibly amused by the incongruity of it. Later in the show, Wilber (on alto) and Adams have another beautiful moment together, playing the two opening 8-bar "A" sections in the theme of Ellington's "Blue Goose." (You can see Billy Mitchell totally broken up over how Pepper navigated the passage.) How far Adams and Wilber have traveled since the 1940s!

I'm especially enthused about this concert because I recently acquired a rare video of the TV show. I'm trying to get it uploaded to YouTube so everyone can see it. How about that sax section?: Bob Wilber, Eddie Daniels, Zoot Sims, Billy Mitchell, Pepper Adams.

In 1978, Adams and Wilber were able to play in several venues together in Nice. They were already touring together as part of an all-star 50th Anniversary Lionel Hampton commemorative gig:

1978

June 28-30: New York: Rehearsals with Lionel Hampton.

June 30: New York: Lionel Hampton gig at Carnegie Hall, with Charles McPherson, Bob Wilber, Ray Bryant, et al, recorded by Sutra.

July 1-2: Saratoga NY: Hampton gig at the Performing Arts Center, with Charles McPherson, Bob Wilber, Ray Bryant, et al.

July 3: Brooklyn NY: Off?

July 4: Travel. Departure for France.

July 5: Travel. Transfer to Nice.

July 6: Nice: Off.

July 7: Nice: Hampton gig at les Jardins des Arenes de Cimiez, with Charles McPherson, Bob Wilber, Ray Bryant, et al., at La Grande Parade du Jazz. Recorded by Radio France.

July 8: Off.

July 9: Nice: Hampton gig at les Jardins des Arenes de Cimiez at La Grande Parade du Jazz. Recorded by Radio France. See 7 July.

July 10: Nice: Hampton gig at les Jardins des Arenes de Cimiez, with guest Dzzy Gillespie, at La Grande Parade du Jazz. Recorded by Radio France. See 9 July.

July 11: Nice: Hampton gig at les Jardins des Arenes de Cimiez at La Grande Parade du Jazz. Recorded by Radio France. See 10 July.

July 12: Nice: Dick Hyman gig, "Tribute to Count Basie," at les Jardins des Arenes de Cimiez, at La Grande Parade du Jazz. Recorded by Radio France.

July 13: Nice: Hampton gig at les Jardins des Arenes de Cimiez at La Grande Parade du Jazz. Recorded by Radio France. See 11 July.

July 14: The Hague: Hampton gig at Prins Willem Alexander Zaal, with Charles McPherson, Bob Wilber, Ray Bryant, et al., at the Northsea Jazz Festival. Recorded by AVRO television.

July 15: Orange, France: Hampton gig at Theatre Antique, with Charles McPherson, Bob Wilber, Ray Bryant, et al.

July 16: Nice: Hampton gig at les Jardins des Arenes de Cimiez with guest Stephane Grappelli, at La Grande Parade du Jazz. Recorded by Radio France. See 13 July.

July 17: Salon-de-Provence, France: Dizzy Gillespie gig, at Cour du Chateau de L'Empri as part of the Festival of Jazz, with Kai Winding, Curtis Fuller, Charles McPherson, Ray Bryant, Mickey Roker, et al. Recorded by Radio France.

July 18: Perugia: Hampton gig, with Charles McPherson, Bob Wilber, Ray Bryant, et al., and guest Dizzy Gillespie, at Umbria Jazz. Recorded by RAI.

July 19: Travel. Hampton band arrives from Italy, possibly by bus.

July 20: Travel. Hampton band arrives in England.

July 21: Middlesbrough, England: Hampton gig, with Charles McPherson, Bob Wilber, Ray Bryant, et al.

July 22: Comblain-au-Pont, Belgium: Hampton gig, with Charles McPherson, Bob Wilber, Ray Bryant, et al. Later, a nearby gig with the Georges Arvanitas trio.

Did Wilber and Adams see each other again after this 1978 tour? Did Bob reach out for Pepper when he heard that Pepper was dying of cancer? Pug Horton told me that Wilber greatly admired Pepper. I think she was referring to both personal and musical admiration. These are just some of the questions I'm eager to ask Bob Wilber. More soon! Have a great week.

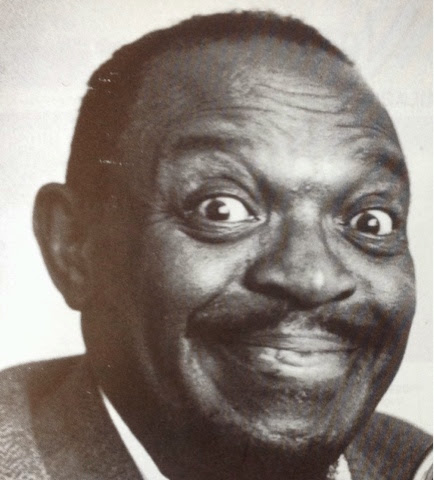

(Bob Wilber)

(Adams in London, at the Ephemera

photo shoot, September, 1973)