Showing posts with label Rex Stewart. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Rex Stewart. Show all posts

Sunday, March 4, 2018

Pepper Adams Biography News

© Gary Carner. Copyright Protected. All rights reserved.

A belated happy New Year to everybody! My apologies to those who have been awaiting a post from me. Yes, I've been away from the blog for some time. My life has been a little chaotic job-wise, though things have sorted themselves out recently.

I'm very pleased to announce that the first half of my Pepper Adams biography is now finished. I completed it a few days ago. It's about 100 pages. I began writing around the middle of April, 2017, upon my return from lecturing at four colleges in Utah. Looking back, I'm still amazed how I got all this done in eleven months. It sure helps to have 34 years of notes! During the next four weeks I'll be editing the manuscript, and going over my Pepper Adams interview transcript and listening to about 25 interviews, just to be sure I don't leave any important things out.

Here's an overview (finding aid) of Part I, what I call "Ascent":

Ch. 1:

Charlie Parker at the Mirror Ballroom

Move to Detroit, Rochester NY vs. Detroit

Skippy Williams

Arrival in Detroit, race relations

Detroit in the 1950s

History of Detroit, 1700-1900

History of Detroit, 1900-1950

Grinnell's

Lionel Hampton

Wayne University

The Music Box, Little John and His Merrymen

Getting the Berg Larsen and Selmer, Detroit's baritone history, Beans Bowles

Ch. 2:

Pepper's father in Detroit

Paternal genealogy

Family's musical roots

History of Rochester

Early life in Indiana, move to Rochester

Age 4-9, father's death

War years

Rochester musicians during World War II

Age 10-12, Everett Gates

Duke Ellington at the Temple Theatre, Rex Stewart, trip to Seattle

Ellington, Skippy Williams, classical music

Importance of elders (especially Rex Stewart), Duke Ellington

Raymond Murphy, Bob Wilber

John Huggler

Isolation

The Elite

John Albert

Ch. 3:

Service in the U.S. Army, Korean War

The Blue Bird Inn

The World Stage

The West End Hotel, Klein's Show Bar

Detroit's jazz history

Thad Jones, Wardell Gray, baritone players on the scene

Obscure Detroit jazz musicians

Pepper's personality, Detroit pianists

Maternal genealogy

Detroit musical education

Detroit's outlier jazz generation, Malcolm Gladwell outlier concepts related to Pepper

Pepper demo played for Prestige and Blue Note, Pepper sits in with Miles and Rollins

Stan Getz story, Pepper moves to New York City

I met with my trusted webmaster, Dan Olson, last week. We're planning important upgrades this year to pepperadams.com. New context will be added to "Radio Interviews" and "Big Band Performances." A link to a new WikiTree genealogy of Pepper Adams is planned.

I had to wipe clean the hard drive on my iPad a few months ago. By doing so, I lost my trusty app for Blogspot. If anyone has a recommendation for an app I can use that DOES NOT ask for my Google password, please let me know. It will help me format future posts.

I did submit my first section from Ch. 3 about Pepper's experience in the U.S. Army for publication in 2019. I'll let you know if it's approved. I'm

Sunday, June 25, 2017

Pepper Biography News

© Gary Carner. Copyright Protected. All rights reserved.

Somehow this past week I wrote a complete first draft of Chapter 2 of Pepper's biography. I had so many pages of notes from other times that I wrote about him or prepared college lectures. The chapter covers the period 1930-1947 and also dives into (as I discussed last week) Adams' parental genealogy. On the genealogy, I added more details about the derivation of the Adamses, all the way back to the Eleventh Century, and some more information on just how tough a dude his sixth great-grandfather, James Adams, was: how he survived the Battle of Dunbar, his march and incarceration, the voyage to the New World and his servitude. James Adams' grit and determination is part of Pepper Adams' DNA.

Here's how the chapter falls:

1. Father's history

2. Genealogy

3. Family music history

4. History of Rochester, New York

5. The move to New York, 1931-1935

6. Pepper, 1935 to his father's death in 1940

7. Rochester war effort

8. 1940s Rochester jazz scene

9. Pepper, 1941-1944

10. Duke Ellington and Rex Stewart at the Temple Theatre; its many implications

11. Raymond Murphy taks about Pepper

12. Jack Huggler talks about Pepper

13. The Elite

14. Isolation

15. John Albert talks about Pepper Adams

Here's an excerpt from the chapter (without footnotes):

Although Adams was still playing in the New Orleans style, his taste in music was already very well developed in 1944.

I was studying more classical music at the time. Although I enjoyed jazz, which I listened to on the radio, which is what you did in those days, it was really classical music which interested me first. Then, when I started to hear Ellington and all those chords and voicings I knew immediately: . . . Debussy, Ravel, Elgar, Delius, the tonal palettes of twentieth-century music were all there. You know, the rough kind of excitement of the Basie band could be a lot of fun and I certainly liked them as soloists but Duke’s band was an entirely different ball game.”63

“Don’t put them next to nobody else,” cautioned Skippy Williams about the Ellington band.

That band, you couldn’t touch them! [Duke] would go back and get some old tricky things like “Caravan” and those kinds of things. He could put some chords on you. They would put some double augmented chords on you, six-note chords, and they would stretch it out in such a way, man, it would sound like five bands were swinging. He would change the chords and make them much heavier. Say, for instance, if you’re making C double augmented it would be C-D-G flat-A flat-B flat and he knew just where to put them to broaden the sound.64

“I was at a restaurant next door to the theater there downtown in Rochester,” said Williams. “Pepper came in and he told me he had heard me play and he liked my playing. He said he played tenor sax. . . . Back when I met him,” Williams continued, “I had taken Ben Webster’s place in Duke’s band. He was very enthused about that.”

I spent as much time as I could. He was working at a shoe store or something. . . . He was asking me about my tone and I told him some certain tricks, how to build his chops up. Well, see, a lot of guys, they try to use their lip a certain way. They don’t let the horn get the right, true sound. You got to let the reed do more vibrating. You have to know how to blow and how to use your belly. . . . He said, “Can I bring my horn by?” I said, “Sure. You can come by any time. . . .” He asked me, “How do you memorize all those things? I never see you looking at the music.” I said, “Next time, come up and look.” He looked up there. They had comic books. We carried about thirty or forty comic books at the time. People think, well, we’re reading Duke’s music but we’d be up there playing like hell and everybody’d be reading comic books.65

Saturday, August 29, 2015

Now Hear This

© Gary Carner. Copyright Protected. All rights reserved.

I heard back from Pug Horton. It turns out that she and Bob Wilber have a son that lives in Atlanta. They expect to visit him sometime in 2016. It looks like my interview with Wilber will be put off until that time. Apparently, he prefers to do it in person. Something to look forward to, for sure!

I just found Pepper Adams' very first 8-track jazz "olio" that he put together. (See https://instagram.com/p/6-7Bfzpnmp/?taken-by=pepperadamsblog.) Adams assembled about 40 of these collections to enjoy while motoring around to gigs, etc. Since this first one includes Dedication and Consummation from the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis date Consummation, I figure that Pepper started making these particular sets sometime in late 1971, when the LP was likely released. If these were the first things Pepper made on 8-track, then he would have purchased his Wollensak-3M 8-track (see https://instagram.com/p/rm4zHfpnj3/?taken-by=pepperadamsblog) recorder sometime that year--that is, if he didn't make a bunch of 8-track classical recordings beforehand. What's interesting about this first selection of tunes is the titles he chose. Here's the roster:

1. Duke Ellington: Fade Up

2. Tony Coe: Regrets

3. Pepper Adams: One Mint Julep

4. Thad Jones-Mel Lewis: Dedication

5. Yusef Lateef: Ma, He's Makin' Eyes at Me

6. Barrry Harris: Like This

7. Duke Pearson: Tones for Joan's Bones https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=vICb0Lggdnc

8. Billy Mitchell: A Little Juicy

9. Bud Powell: Dusk in Sandi

10. Duke Ellington: All Day Long

11. Pepper Adams: Port of Rico

12. Blue Mitchell: Smooth as the Wind

13. Thad Jones-Pepper Adams: Bossa Nova Ova https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=CPmhYbMdt5s

14. Thad Jones-Mel Lewis: Consummation

15. Joe Henderson: Without a Song

16. Pepper Adams: Azurete

17. Duke Ellington: Rock Skippin' at the Blue Note

18. Music, Inc (Charles Tolliver/Stanley Cowell): Ruthie's Heart

19. Pepper Adams: Moten Swing

What can we make of this? Of the 19 cuts, 1 (#18) was previously unknown to me, 3 are Ellington, 5 are Pepper's dates as a leader or co-leader, 7 are recordings he appears on (it would have been 9 had he not missed most of the Consummation recording), and 12 are led or co-led by Detroiters. I'm especially taken that Pepper would include the four unissued Motown cuts that he did in 1963. Those wonderful tracks, with arrangements by Thad Jones, remain unissued to this day. I've been trying to get Universal to release them.

Adams made his second 8-track jazz tape with these tunes (see https://instagram.com/p/6-pNA9JnhE/?taken-by=pepperadamsblog):

1. Hank Jones: Fugue Tune

2. Joe Henderson: Invitation

3. Charlie Parker: Repitition

4. Yusef Lateef: Quarantine

5. Duke Ellington: Just Scratching the Surface

6. Tommy Flanagan: Solacium https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=iUeuB7K8PCc.

7. Billy Eckstine: Air Mail Special https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=l5Lq4h9Hhaw

8. Tony Coe: Together

9. Dizzy Gillespie: Serenade to Sweden

10. Ben Webster: Did You Call Her Today

11. Mike Westbrook: Portrait

12. Rubberlegs Williams: What's the Matter Now

13. Duke Ellington: Mr. Gentle and Mr. Cool

14. John Coltrane: Time After Time

What can we make of these cuts, especially as compared to #1? More Ellington and Coe, and, to be sure, a bunch of Detroiters again, plus another surprise cut for me by Rubberlegs Williams. Thank goodness for YouTube, here's the tune: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=CvGNw9xKp70. It's a Charlie Parker feature from 1945. Flanagan's Solacium (whatever does that mean?) is new to me too. It features early solos by the leader, Coltrane, Idrees Sulieman and Kenny Burrell. The Eckstine tune has Leo Parker on baritone (on the studio version), though I'm not sure if he's audible. This is one of the first great bop bands. This a smoking live version, possibly not what Pepper chose, but presumably with a fantastic Fats Navarro solo and Budd Johnson on tenor. What a great chart. Did Johnson write it?

Shall we check out one more? Here's Pepper's sixth 8-track olio:

1. Duke Ellington: Perdido

2. Freddie Hubbard: Latina

3. Rex Stewart: Georgia on My Mind

4. Bud Powell: Hallelujah

5. Duke Ellington: Primpin' for the Prom

6. Herbie Hancock: The Prisoner https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=NiCsgkhTp7Y

7. Rex Stewart: Alphonse and Gaston https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=PRWg53dOWpw

8. Duke Ellington: Tootin' Through the Roof

10. Thad Jones: Let's Play One

11. Elvin Jones: Tergiversation https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=Mtg_GPKZrJg

12. Pepper Adams : Carolyn https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=eTVldpGemsg

13. Bud Powell: I Want to Be Happy

14. Duke Ellington: Boy Meets Horn

15. Louie Bellson: The Jeep is Jumpin'

16. Ben Webster: The Days of Wine and Roses

How about that exchange on #7 between Cootie Williams and Rex Stewart? #9 surprised me: Quite free, and with no Surman bari solo.

What fun it's been getting into the heart and mind of Pepper Adams! I hope you've enjoyed the ride.

Saturday, May 16, 2015

Adams Biography, Straight Ahead

© Gary Carner. Copyright Protected. All rights reserved.

This week has been a busy one for me. Apart from the heavy demands of my day job, all of my free time has been put into polishing up Chapter 1 of Pepper's biography. For the last six weeks or so I've been thinking about Pepper's boyhood and how significant elders stepped in after the early death of his father. The music of Duke Ellington and Rex Stewart (one of those elders) has been playing non-stop in my car--and, now, constantly in my head--as the unofficial soundtrack to my work.

The first chapter is in tip-top shape now, though I endless tweak things (a writer's curse) while I await word from my gifted readers Ron Ley and John Gennari. For the Prologue, they recommended other topics to discuss, as well as grammatical issues to repair. I expect much the same this time around. Then, it's back to writing.

Next week I'll start listening to Pepper's Duke Ellington 8-track material, then eventually move to his Charlie Parker and Tommy Flanagan compilations. Bird, of course, was a huge influence on Pepper, but so was Flanagan. Tenor saxophonist Bill Perkins pointed out in an article in Cadence that Pepper was playing Flanagan lines. Can anyone recommend specific Flanagan solos that I should check out that are markedly similar to Pepper's playing style? I know that Chicago drummer George Fludas felt that the head of Pepper's composition "Conjuration" was very much written in a graceful Flanagan/Detroit feel, but how about some solos to compare? So far, I'm only hearing a similarity when they play fast double-time passages.

While tweaking Chapter 1, I'll move on to researching Chapter 2. That chapter will involve discussing Pepper's father, his side of the family and Pepper's early days in Rochester, New York. It will probably dovetail into a long discussion about Detroit. I'll need to go back and listen again to many interviews I conducted more than twenty years ago. That will be lots of fun and quite nostalgic. I shared many phone calls with so many great musicians, many of whom are no longer with us. In addition, I'll be reaquainting myself with the music of Coleman Hawkins, Don Byas, Art Tatum, Wardell Gray and Sonny Stitt, all important early influences on Pepper. I don't expect a first draft of Chapter 2 for quite some time, but you never know!

Saturday, April 18, 2015

Walkin' About: Strolling Through Pepper's Chronology

© Gary Carner. Copyright Protected. All rights reserved.

I hope you enjoyed reading the Prologue to my forthcoming Pepper Adams biography that I posted last week. I've re-read it a few times since then and I'm pleased with it. It took me several months and numerous revisions to get it to this point, and this after first writing an entirely different draft more than a year ago. Two of my distinguished readers, John Gennari and Ron Ley, have given me the "thumbs up" on the new version. That gives me the assurance that I can finally move on to Chapter 1. To that end I've been pulling together my notes about Rex Stewart and listening again and again to Pepper's 8-track material featuring Rex with the Ellington band.

How many of you have listened to Rex Stewart? I'm quite familiar with contemporaneous Ellington trumpeter and growl master Cootie Williams. Somehow I never really knew much about Stewart until now. Rex is terrific! He had an impressive plasticity with his time and could play with tremendous drama, power and technique. But mostly it's the playfulness and joyousness and incredible creativity that makes him so compelling. Like Cootie, Rex's half-valve inflexions and smears add a "badness" and soulfulness to his solos. They serve as such a beautiful counterpoint to his exuberance and sometimes wild sense of humor. I'm starting to understand why Pepper loved his playing. Rex, above all else, was a stylist.

I'm also reminded of what Kenny Berger wrote in this blog a few months ago about Rex's influence on Thad Jones. Pepper, for his part, was a huge Rex Stewart fan for at least ten years before he met Thad in the early '50s. One can only imagine how their mutual affection for Rex Stewart, among other things (such as Pepper's close friendship with Elvin, Thad's younger brother), must have brought them quickly together as soulmates. Pepper and Thad's relationship was complicated. It will be explored in the biography.

Besides signing off on the Prologue and getting deeper into Rex Stewart, I've also been updating "Thaddeus." That's the part of Pepper's chronology that begins with the early 1965 formation of the Thad Jones-Pepper Adams Quintet and ends with Adams leaving Thad/Mel in late August, 1977. The new version has been posted. Please check it out: http://www.pepperadams.com/Chronology/Thaddeus.pdf

Although the Chronology can be easily overlooked as a less sexy part of pepperadams.com, it's really the bedrock of the site and of all my research. I can't begin to tell you how many times I've consulted the Chronology when I'm assessing aspects of Pepper's life. Because new data is always being discovered--ads for gigs, broadcasts, audience tapes, memorabilia--you can expect that I'll be continually updating it over time. The new version of "Thaddeus" has been enlarged about 10% with new discoveries and deletions. At around 50 pages, it accounts for at least a third of Pepper's entire five-part Chronology. Fortunately, now that "Thaddeus" is updated, I can turn to more manageable sections and get them out soon.

One thing that I'd like to add to the Chronology, if it's possible to build it directly into the site, is some kind of search function. When the database was on my old Macintosh laptop, it was really quick and easy to do searches of musicians, dates or whatever was needed. If I wanted to check all the times Pepper recorded for a certain label, for example, or check how many times he recorded with a certain musician, or even see all the times he visited a certain location, the computer did it effortlessly. Now, with an iPad, I have to convert my original PDF files to iBooks and search it there. It's doable but not as good as if I could do it directly at pepperadams.com.

Can you do Chronology searches on your computer? Please let me know. I'll be sure to discuss this with my trusty webmaster. If there's other things you think can improve the utility of the Chronology or other parts of the site, please volunteer that too.

Regarding the update of "Thaddeus," a few things attracted my attention. One was learning that Duke Pearson returned to New York from Atlanta in late November, 1972 to reconstitute his big band. From what I can tell, he kept his steady Half Note gig until the Summer of 1973.

Another thing that struck me was that Pepper participated in a number of benefits. Whether it was to assist the family of writer Ed Sherman, perform at the Dave Lambert Memorial Concert, participate at a benefit to restore the Apollo Theater, etc, Pepper was involved with the community.

Many sporting events are listed in "Thaddeus," thanks to Pepper's penchant for saving all sorts of memorabilia. When possible, links to my Instagram site show the original ticket stub or program. Pepper especially liked football and hockey but enjoyed spectator sports of all types.

I was reminded about the one-month gig Pepper did in New York with Ella Fitzgerald in 1967. Ironically, that was at a time when Tommy Flanagan was not her music director. Tee Carson was her pianist.

I also forgot that my reader, Ron Ley, was Pepper's Best Man. Imagine that! Ley's comments will be some of the most compelling in the biography. As you can tell from his quote in the Prologue, he was very close with Pepper and witnessed him at pivotal moments.

Pepper's early role in jazz education also jumped out at me. With Thad Jones, Tom McIntosh and others (such as Herbie Hancock and Donald Byrd), starting in the late 1960s Pepper was involved with the Wilmington Band Camp. Pepper also participated at the National Stage Band Camp.

The amount of "hit-and-runs," with those long, early-morning bus rides back to New York, was pretty startling. Adams' many gigs directly after long airplane flights, too, was a pretty frequent occurrence. The touring jazz life is grueling. Add to the lack of sleep cigarettes, alcohol, late nights and financial twists and turns and you get some sense of why so many jazz musicians, such as Pepper Adams, died far too young.

Another thing I was reminded of was the finite amount of time Pepper spent in the New York studios. He only got involved doing session work in about 1967. His participation, though limited by not doubling on bass clarinet, lasted until about 1976. He mostly did overdubs, especially on CTI dates in the early 1970s. But he was on some unusual projects, such as those by The Cowsills, Sonny Bono, The Nice and others. Of course, he also appears on many of the great early Aretha Franklin tracks for Atlantic. These were done as overdubs. He had no idea at the time for whom the music was crafted.

The number of gigs Pepper had in Baltimore for the Left Bank Jazz Society surprised me. There must be at least ten, maybe more? Also, the amount of work Pepper did with David Amram over the years is substantial.

If anyone knows of the 2 June 1974 WBAI interview that Pepper did in New York with Larry Davis, I'd really like to hear it. That and a Phil Schaap telephone interview done on Mingus' birthday for WKCR (New York) are two radio interviews I'm eager to hear.

The length of "Thaddeus" is surprising. But, then again, Pepper's date books and memorabilia (including many band itineraries) helped me chronicle that part of his career more than any other. The sheer number of gigs and presumed gigs--at colleges, in California, or those many "possible" nights at the Vanguard--is staggering. Because so many remain unsubstantiated, much work remains to prove they actually happened. Please email me any discoveries.

(Thaddeus Joseph Jones)

Saturday, January 17, 2015

Pepper Adams Biography

© Gary Carner. Copyright Protected. All rights reserved.

I've begun writing the second volume. I've modified and signed off on the Epigraph, Prologue and first chapter and I continue to build the Recommended Listening section. Perhaps some of you have noticed that every few days I've been sneaking in my listening choices on my Facebook page? So far, I've posted around seven tunes and videos. Many more are to come, of course. It's been fun listening again and adding them. Today I listened twice to one of Pepper's great masterpieces: Pepper Adams Plays Charlie Mingus.

As for the biography, I'll post the Epigraph below, then the Prologue next week and Chapter 1 in two weeks. After that, you'll just need to wait and read the book! Chapter 1 sets things in motion with a rationale for why Pepper is an important figure. It's intended to entice those not faamiliar with him and his work. It leads into Chapter 2, something I'm developing, which might be a discussion of his father or other father figures, such as Rex Stewart. The Prologue discusses when I met Pepper and how my work on Pepper came to be.

As for the biography, I'll post the Epigraph below, then the Prologue next week and Chapter 1 in two weeks. After that, you'll just need to wait and read the book! Chapter 1 sets things in motion with a rationale for why Pepper is an important figure. It's intended to entice those not faamiliar with him and his work. It leads into Chapter 2, something I'm developing, which might be a discussion of his father or other father figures, such as Rex Stewart. The Prologue discusses when I met Pepper and how my work on Pepper came to be.

Here's the Epigraph, stated to me in a Thelonious Monk seminar I took many years ago in Blake's Brookline, Massachusetts apartment:

How many musicians out there are really different?

- Ran Blake

Saturday, October 25, 2014

Rex Stewart and Young Pepper Adams

© Gary Carner. Copyright Protected. All rights reserved.

On March 3-5, 1944 thirteen year old Park Adams skipped school three nights in a row to attend Duke Ellington's entire run at the Temple Theatre in Rochester, New York. Adams was already playing piano, saxophone, clarinet and enjoying jazz programs on the radio. Starting in 1936, six-year-old Adams listened to Fats Waller's daily 15-minute afternoon radio show. In 1938 Adams tuned in to John Kirby's program featuring his sextet. And in 1940 he caught Fletcher Henderson's late night broadcasts originating from Nashville.

Though Adams' parents didn't play musical instruments, they owned a piano and a broad selection of 78 rpm records. Because of that, Adams was exposed very early to both jazz and classical music. By seventeen he was familiar enough with the history of the classical repertoire to get hired in the Classical Music Record Department of Grinnell's in downtown Detroit.

Adams was especially drawn to the symphonic music of his era and at a young age developed a taste for dissonant harmonies. Although Adams was still playing in the New Orleans style, his taste in music was already very well developed in 1944. One can imagine how excited Adams must have been to hear the Duke Ellington Orchestra in a concert settting.

Adams was especially drawn to the symphonic music of his era and at a young age developed a taste for dissonant harmonies. Although Adams was still playing in the New Orleans style, his taste in music was already very well developed in 1944. One can imagine how excited Adams must have been to hear the Duke Ellington Orchestra in a concert settting.

The Temple is a movie palace built in 1909 at 35 Clinton Avenue South in downtown Rochester. On the third and final evening of the Temple engagement, Ellington trumpeter Rex Stewart was curious about the enthusiastic, short-haired white kid with horn-rimmed glasses he noticed sitting by himself each night in the balcony. Intrigued, Stewart made his way upstairs, introduced himself, then brought a no doubt exasperated Adams backstage to meet Ellington's illustrious musicians, including Johnny Hodges and Harry Carney. While there Adams overheard Frederick Delius recordings being played by Ellington that commentators have reported Duke was listening to at that time.

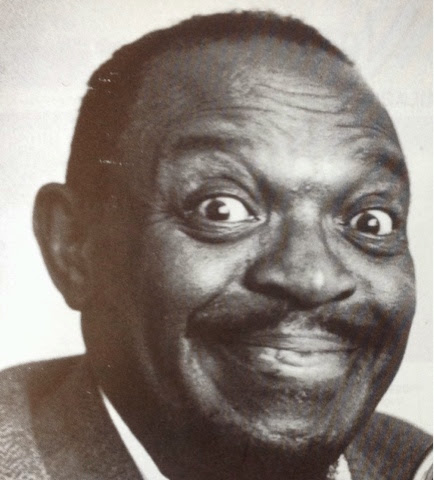

(Photo by Valerie Wilmer c. 1966)

It's hard to overstate how valuable this encounter was for Adams, or the role Rex Stewart assumed as a lifelong father figure and influential elder. Should we assume Stewart sought out young Park Adams because he was sitting by himself or presumably an anomaly in a mostly black audience? While maybe part of the equation, I believe Stewart was honoring this provocative teenager, who at the time must have been from Stewart's perspective a very special young man for going out of his way to scrape together enough money to attend the Ellington orchestra each night. Stewart was also continuing the important tradition of an elder musician supporting a young aspiring one, something that (to its detriment, I think) has mostly died off in jazz.

Consider for a moment the context. Just a few years earlier, Adams' father had died at the age of 44. Adams, an only child, was already a survivor of the Great Depression like so many who were born after 1929. His father's death, when Adams was nine, only intensified the ordeal.

The Depression had destroyed Adams' parents' way of life. It robbed them of their Detroit home and separated them for nearly four years while his father traveled throughout the U.S., looking for any work he could find. Worn down by the strain of scratching out a living, his father suffered his first heart attack in 1934 in Rome, New York, partly from the excitement of his family finally being reunified. In theory, it was intended to be a time of great joy. Instead, Adams' father lived out the remainder of his life a frail and unfulfilled man.

The Depression had destroyed Adams' parents' way of life. It robbed them of their Detroit home and separated them for nearly four years while his father traveled throughout the U.S., looking for any work he could find. Worn down by the strain of scratching out a living, his father suffered his first heart attack in 1934 in Rome, New York, partly from the excitement of his family finally being reunified. In theory, it was intended to be a time of great joy. Instead, Adams' father lived out the remainder of his life a frail and unfulfilled man.

At the Temple Theatre, Rex Stewart's profound act of kindness--his mentoring of Pepper and adopting the role of a father figure--must have filled a void in Pepper's life. It was certainly the most transcendent event of his boyhood. Very soon after meeting Stewart, Adams took a few tenor sax lessons with Skippy Williams, the tenor saxophonist in Ellington's band that Stewart introduced Pepper to backstage. Williams was the saxophonist who first replaced Ben Webster, prior to Al Sears. (I interviewed Williams, by the way, and hope to share that with you in a later post.)

That night at the Temple put in motion Adams' lifelong love affair with Ellington and Strayhorn. (Listen to Pepper's original ballads, such as "I Carry Your Heart," and you'll hear Pepper's profound debt:

http://www.pepperadams.com/Compositions/compList/ICarryYourHeart/index.html#anchor)

Pepper's close friend Gunnar Windahl told me the following about Pepper:

http://www.pepperadams.com/Compositions/compList/ICarryYourHeart/index.html#anchor)

Pepper's close friend Gunnar Windahl told me the following about Pepper:

"Every day, I think, he listened to Duke Ellington. Duke Ellington meant a lot to Pepper. I remember we were in Gothenburg. After a gig there we came into my room. I had a half a bottle of whisky and we sat talking. With my blue eyes, and as an overreacting person before such a star as Pepper Adams, I managed, 'Who is the best musician in the world, Pepper? Who do you consider the most interesting and underrated?' He said the most interesting and underrated musician in this business is Rex Stewart.' I was a bit taken aback. Then Pepper said that he seen Rex just before he died and that Rex was very disappointed that he wasn’t more recognized. I think Pepper identified with Rex’s destiny."

Pepper's life mirrored Rex Stewart's. Rex had success in the mid-1930s and '40s as one of Ellington's great soloists, then languished. Adams, according to bassist Percy Heath, was a sensation in New York when he first arrived in early 1956, created a similar stir in California in early 1957, had an influential quintet with Donald Byrd from 1958-1961, then languished. I don't mean "languished" as a pejorative term related to their musical growth or achievements but simply as a term for how much they struggled financially and how little attention they received from record companies and the international press.

Pepper, for obvious reasons, identified with struggling artists, whether it be Rex Stewart, the painter Lyonel Feininger or the composer Arthur Honegger. For Adams they were all very special because, like himself, they were unique, accomplished, had struggled financially throughout their careers and were overlooked.

Other than his very close bond with Stewart, what is it about Stewart's playing in particular that Pepper Adams admired? His off-the-wall humor, for one thing, with oblique phrases coming seemingly (as Pepper put) "out of left field." You can grasp Stewart's almost wacky sense of humor in his most well-known Ellington feature Boy Meets Horn:

Stewart was technically brilliant and harmonically adventurous. Listen and watch these three clips:

1. Duke Ellington's 1938 Braggin' in Brass: http://youtu.be/M_bFnaiyAZM

2. Nick Travis and Rex Stewart perform "There'll Never Be Another You" (1958) from the TV show Art Ford's Jazz Party: http://youtu.be/mzsJUbKwIN8

3. Also, from the legendary 1957 CBS TV show "The Sound of Jazz" Rex takes his solo on "Wild Man Blues" just after the 8-minute mark. It's replete with numerous musical paraphrases. Perhaps that's another Rex Stewart influence on Pepper? Rex's irrepressible joy is obvious throughout, especially when he openly laughs after his first four-bar statement: http://youtu.be/vo7qiXkTu4s

Also, check out Stewart's book Jazz Masters of the 30s. It's a collection of his writings that were collected posthumously. Like Pepper, Rex Stewart was very literate:

Pepper Adams was always very guarded with his emotions. According to his widow, Claudette, Pepper used music to get his emotions out and was not one to readily share the intimacies of his feelings with anyone. But Rex Stewart's death in 1967 was too much for him to contain. According to Montreal radio host Len Dobbin, Pepper broke down and wept when Dobbin told him that Stewart had died.

Saturday, September 27, 2014

I Remember Pepper: Gunnar Windahl Remembers Pepper Adams

© Gary Carner. Copyright Protected. All rights reserved.

Swedish psychoanalyst Gunnar Windahl was one of Pepper's dearest friends. His recollection below gives an extraordinarily rich and detailed portrait of Pepper Adams. Windahl tape recorded his remembrances and sent me a cassette in the late 1980s. I transcribed it about 10 years later.

I was invited to come over to the U.S. I think it was in April, 1979. That was the first time I was in the U.S. Pepper and I were supposed to go within a few hours of each other from Kastrup in Copenhagen. Pepper was on a tour in Norway and he showed up rather early in the morning when I was in the bar. I saw immediately that he was very tired, to say the least. I offered him schnapps and so on. Suddenly I saw that he was heavily drunk. He was in a good mood and somehow we came onto the topic of Oscar Pettiford. He told me a good story about when he and Oscar Pettiford were out riding in Long Island or somewhere and Oscar said that they should go to his Indian friends. (He was an Indian.) So they ended up in an Indian tent drinking “firewater.” It was a long and interesting story that the bartender was caught up in; he forgot serving the other customers at the bar. It was very early: nine in the morning or something, but Pepper had no sense of the time. His timing, when it came to playing, was impeccable. When it came to drinking it could slide away a bit.

Pepper was supposed to go a few hours before me. We went out to the gate a bit swaggering. When we came to the gate Pepper’s plane was overbooked so he couldn’t go. Pepper yelled at the hostesses and they were terrified. I heard expressions I never heard from him before or since but he couldn’t get on the plane. He had to fly to Stockholm, stay overnight at a hotel and return the next day. My plane was not overbooked so I flew ahead to Kennedy Airport, where Claudette fetched me. We went to their house at 8715 Avenue B in Brooklyn, where I got introduced to Claudette’s son, Dylan, a very nice kid. The next day we picked Pepper up at the airport.

I stayed for five or six weeks and I had a good opportunity to study his routine. It was not always joyous. You could see he had no job for long periods of time. He went smoking around, reading and so on. When we approached the cocktail hour his frowning forehead cleared up and he went deep into the Kentucky bourbon bottle. Just two drinks before dinner: that was a very rigid rule in that house. Really, it was like two bottles of hard liquor! He could really pour a drink, I assure you. I was not accustomed to a very fast drink. I was deadly drunk when I came to the table.

Sometimes I was very sad because he had no job and you saw that he longed for a call. But now and then he had a gig and I went with him: to Washington, up in Connecticut and, of course, in New York City, but not the main places. I think Pepper was very disappointed that he wasn’t invited to play at Fat Tuesday’s more often, at the Village Vanguard, Seventh Avenue South. We talked about that when we were a bit drunk. Otherwise, I didn’t dare take up the topic.

Claudette had alimony from her ex-husband and I think they lived a lot upon that. I don’t think Pepper was happy about it but he never mentioned anything to me. Still, they were very happy together and we had a very good time. I really liked it there. Claudette prepared very delicious food. I think Pepper needed to have a family at that time. It meant a lot to him. A few years later it broke. That was terrible.

It was interesting to stay at Pepper’s house. He had a very good record collection and I taped a lot of them. Every day, I think, he listened to Duke Ellington. Duke Ellington meant a lot to Pepper. I remember we were in Gothenburg. After a gig there we came into my room. I had a half a bottle of whisky and we sat talking. With my blue eyes, and as an overreacting person before such a star as Pepper Adams, I managed, “Who is the best jazz musician in the world, Pepper? Who do you consider the most interesting and underrated?” He said, “The most interesting and underrated musician in this business is Rex Stewart.” I was a bit taken aback. Then Pepper said that he seen Rex just before he died and that Rex was very disappointed that he wasn’t more recognized. I think Pepper identified with Rex’s destiny. We say in Sweden that you must have “elbows” to get into the front but Pepper didn’t have that and he knew it. He would never push himself. He expected people to phone him. I think he felt a lot of dishonesty from fellow musicians that didn’t hire him and took other musicians at a lower rate.

I recognized, of course, that he had a very good book collection. He read a lot and was very versed in literature and art. He was a very intelligent and clever man. I learned a lot from him. In a way he was a bit too much taken aback by me being a professor. Many times I tried to tell him, “You shouldn‘t take that so seriously.” He was much more into history than I was. I told him so. I think it meant a lot for Pepper to get confirmation that he was an intellectual. He mentioned often that his parents were poor and couldn’t send him to college. I think he, all by himself, became “professional,” besides just the music. I was very much impressed by his knowledge of many things. He was a fantastic man.

I arranged a tour in Sweden for Pepper in the summer of ’79. It was no big deal. I fixed gigs in Malmö, Gothenburg, Stockholm and so on. Claudette and Pepper stayed in my apartment in Malmö. We had a very good time then. Of course the booze could be a problem for Pepper. Once we played at a place called Stampen in Stockholm. He was drinking schnapps during intermission and he was very drunk during the last set. I didn’t like that. It was like having your own father drunk before other people. Sometimes Pepper was like a father for me but he didn’t care. But Claudette was, of course, not very happy about it. Al Porcino told me once that Claudette accompanied Pepper during the tours in Europe and when she left for the U.S. he started drinking with Thad. Sometimes they had to change the “book” when Thad realized that Pepper was drunk, that he couldn’t play any solos.

Pepper spoke more freely after a few glasses of liquor. He was no easy-speaking man when he was sober. It was not that easy to get in touch with him. A few sentences, then he picked up a cigarette and lit it. But after a few glasses he thawed and was very easy to speak with. He very generously presented good stories from his fantastic life. That Claudette had to behave like a policeman sometimes so he didn’t drink too much was, of course, a problem. When it came to my part, it was sometimes a bit difficult if I should present a new bottle or should refrain.

Pepper exposed me to other musicians. For example, if he had Rex Stewart as his favorite musician, another musician high up on the list was Tommy Flanagan. I can’t remember how many times he tried to remind me that Tommy Flanagan is “the best.” Of course, Pepper’s other favorite pianists were Sir Roland Hanna, Hank Jones, Jimmy Rowles. He admired them very much and we played them often in his house in Brooklyn. But sooner or later he came back to Tommy Flanagan. It was very interesting that he knew so many people.

When he was out playing, I got the impression that other musicians liked to hear him. I remember once Sam Jones telling me how much he admired Pepper. It was more backstage talk in some sense. It was not said explicitly but they admired him.

Sometimes Roland Hanna would be confused about Pepper, I think. Pepper was too much for Roland. I think Roland was never safe with him. Pepper was too clever for him or something. When I presented the lead sheet for “Doctor Deep” to Roland he was a bit embarrassed, I think. He didn’t want to play it on the piano. Sometimes I see that with Tommy too. Maybe they were uncertain about my relationship to Pepper, how close it was. Maybe that, I don’t know. But I think it’s something else. I think he was a bit of an enigma for them. He knew very much outside the usual areas of the jazz musician’s world: politics, literature, art and so on. I think they were a bit uneasy about it. I think no one musician was very close to him. He had no real friends among musicians, at least at the time I knew him.

Pepper was in Sweden in 1983. He was playing in Stockholm at Skeppsholmen with Monica Zetterlund. I don’t know but I think they had a relationship in some way. We met at the Korsal Hotel, together with Charlemagne and Hans Fridlund. Pepper was rather drunk and I remember I was with a friend of mine. That was the first time I saw him really drunk.

At that time I got a letter from Claudette that upset me a lot. His blood counts were not very good and he had to stop drinking. But I couldn’t see any of that when I met him. That was the first sign of their relationship getting worse. There I was, not very optimistic about the future when it came to his marriage, but we had a good time in Stockholm. He played very well there.

That was the last time I saw him, as far as I could see, as a “whole” person. The next time I saw him in Sweden was the disastrous time when I discovered his cancer. Before that, of course, he got his leg broken. At that time I understood that their relationship deteriorated very much. When I called him, when he sat there in his wheelchair, he was not very happy. I didn’t understand what was going on. Claudette didn’t write me. As I understood, she was not in the house. He came to Sweden afterwards, walking with a limp. He wrote me long before he was supposed to be in Stockholm in March, ’85. He wanted me to come down and see him. He was supposed to play in Mosebacke and I arranged a gig in Boden up where I live. I took a few days off. I went to his hotel, knocked on the door around noon and was taken aback when he opened the door. I saw that something was wrong with him and it couldn’t just be the leg. He greeted me as a long-lost friend and I asked him how things were in his life. He complained that he didn’t know if he had any house or belongings when he went back to the U.S. I tried to get some clear information about this but he refused.

I didn’t like his look. His eyes were burning. Now and then he coughed, and it was a terrible cough like one with pneumonia. So I said to Pepper, “We must look at that when you come up to Boden.” He was supposed to be there in a few days to play at the local jazz club. They were quite excited about such a star up there among the polar bears! He would come up, I’d fetch him at the airport and he would live at my apartment for a few days. I said, “I have a good friend up there, Chief of the Thorax Clinic. I’ll arrange an x-ray of your lungs and we’ll see what shape it is.” He was very, very grateful for that. He looked relieved.

Then a friend of mine didn’t show up. I had nowhere to sleep in Stockholm so I took the other bed in his room. I woke up very early in the morning and I saw him still asleep. I saw that he slept very uneasily, very much dissimilar to his usual calm way. He hadn’t been drinking. He had slept very well the night before, as far as I could understand. But now he slept with some hectic way of breathing. I was very much alarmed about the situation. Something was wrong.

We got around in Stockholm, though he had difficulty walking. I invited him to restaurants. He played with Rolf Ericson, among other guys there, and he played very well. I went to Boden before him and he came up after a few days. He took a nap in the day. That got me anxious too. He never would like to do that. Before the gig I served a very nice dinner for him with specialties from the Lapp area like reindeer. He very much liked that. Then he played at the local club. We went home, having a few beers, but he didn’t want to drink because of the meeting with Dr. Haugstød.

In the morning he woke me up and we went to the Thorax Clinic. I just lived a few blocks from the hospital. I worked there. I left him there and went home. I took a cup of coffee and half an hour later Pepper showed up and said, “I have cancer in my left lung.” I’ll never forget the reaction I had. I went to the fridge, took a few export beers and drank them down and took a few other beers and drank them down. I didn’t know what to say. He looked at me in a way I had never seen before. The whole thing was terrible. I was supposed to take him to the airport. He was supposed to go to Stockholm and be in a program for the Radio there with just Hans Fridlund and then I think he went to Malmö. I don’t remember exactly what was going on. I was too drunk to get him to the airport so I put him in a taxi. That was the last time I saw Pepper Adams, my old friend. I paid the taxi in advance and ordered the driver to help him with his instrument. He sat laughing in the back seat, not very much alarmed on the surface at least. But I was alarmed. I’m not a medical specialist but I have a lot of friends who are and I knew time was short. In my drunkenness I called Fridlund in Stockholm and told him that Pepper had cancer.

I think when he was in Malmö I talked to Pepper. I was crying on the telephone. I was still drunk. He said, “Pull yourself together, Gunnar. I’m not dead yet.” But I said, “You are my friend and this is terrible.” “You haven’t got a cold,” I told him. “This is serious.” He had the x-rays with him to show his doctors in the U.S. I got in touch with Claudette and she was stunned. I was a mess.

He called me back a month later from the U.S. and wanted to give a report to Haugstød of what they had found in the U.S. I tried to write down all the Latin words. Once I said, “I didn’t catch what you said. I didn’t catch it, Pepper.” “Don’t catch it, for heaven’s sake, don’t catch it!” he said. He was funny. “No, no, I won’t catch it,” I promised him.

When I went to Doctor Haugstød, my friend, and told him that they found oat cell cancer, he shook his head and said, “They shouldn’t treat that. Put him on a steamer to the South Sea where he can play and enjoy some women or something.” He told me, “You can never cure that.” Of course I was very sad about hearing that. I read a lot about that kind of cancer. It’s a diffuse kind of cancer. No one recovers from it. They started the hard treatment in the U.S. We phoned each other now and then. Mostly, I phoned him: “How are you, Pepper?” He said, “Fair, fair.” He was not exaggerating. Once I called him and he was heavily drunk or sick.

He tried to cheer me up all the time. I couldn’t conceal that I was very sad about everything. I was a very close friend. Pepper once told me that I was his closest friend, as close as Elvin Jones was. He had very tender feelings for Elvin. He mentioned him many times. But I think he was disappointed with Elvin too, that Elvin left him and never hired him for a gig. He never told me that but I could read between the lines.

Pepper wrote me a letter then that he was supposed to perform in Zurich a half a year later. I had difficulty getting free to go to Switzerland and meet him. I phoned and said, “Maybe I’ll show up, maybe not.” Pepper tried to persuade me, that this was a fantastic place to play, that they have very good food and so on. I had a lot of things to do and it was not that easy to leave patients and people behind. But of course I should have gone. I regret every day that I didn’t go there because I think he needed me. But I wasn’t strong enough to go. When he came back to the U.S. he wrote me a letter and I could see that he was disappointed with me that I didn’t show up.

One of the last calls I had with him he told a story of a man who left a scribble of paper on his end table. The man was found dead in the morning but the bit of paper said, “I didn’t wake up this morning.” He told such jokes. It was marvelous. He wrote me with a lot of stories. I think I tried to hide them because it was touching to read them and I’m not good at that. The last time I heard him on the phone was just three or four days before he passed away. Claudette answered the phone and then Pepper tried to say something brief. There was not much left and I didn’t know what to say. I just said, “I can’t do anything for you, Pepper.” “I know that. I know that, Doctor Deep. Thank you for calling.” That was that and a fortnight later, I think, I called Claudette and she said that Pepper had passed away very quietly. I had plans to go overseas for Flanagan’s memorial concert in September ’86 but, again, there was something preventing me from doing that. I don’t know what. It was too much, I think.

He didn’t complain during this time. He said sometimes it was terrible. He had a hell of a headache. But he was marvelous, I think. He never complained and I felt very much ashamed when I couldn’t put myself together and was crying a bit. But he was firmer. I think he was stronger. Claudette told me that too. He was really brave.

I warned him many years ago of contracting cancer because of his smoking. He did smoke really heavily. He had no filters on his cigarettes. Pepper did have some blind spots. He didn’t like to see that he smoked too much and drank too much. He didn’t take it in. He looked very destructive to an observer.

When it came to admiration, besides Rex Stewart he mentioned very often Joe Henderson, especially the early Joe Henderson on the Blue Note label. For example, Inan’out and Inner Urge were records Pepper liked very much. Of course, I think the musician he most admired and wanted to live up to was Thaddeus Jones. I remember once when he and Thad had left the band—I think it was in Germany—for a few gigs in Malmö and Copenhagen and Claudette had gone back to the U.S. After playing together in Malmö, Pepper and I sat there drinking whisky. Suddenly he confessed that he felt very much a small little boy compared to Thad and he elaborated upon that topic a bit. He often said that Thad was too much for him in a way. Sometimes he was a bit scared of him, I think.

Pepper took up some pieces Thad wrote very early in the ’50s: “Quittin’ Time,” “A Bitty Ditty.” He went back to Thad’s early production, which he considered masterpieces. But there was a tension between he and Thad. Thad admired Pepper too a lot, I know. Thad told me once that he thought Pepper marvelous, very erudite. When Pepper left Thaddeus’ band, on the surface he said that the reason was that he wanted to play, to be on his own. But I think he was a bit disappointed with the band after Roland left. I got the impression that Pepper didn’t like the last two years or so. I think he considered the band degenerating a bit but he wasn’t explicit on this point.

Of course, Elvin Jones meant a lot to Pepper. He considered Elvin a very close friend and admired him very much. He told a lot of jokes—memories from when they lived together in the Village. Pepper told me how he placed any book in Elvin’s hands and he read it without pause. “Read this, Elvin” and Elvin read it! He read everything. When I first met Pepper in the beginning of the ’70s he was a bit uneasy about Elvin’s shyness and considered him drinking too much. He told me that it was very difficult to get in touch with Elvin. He was very withdrawn.

We, of course, discussed Pepper’s records. Reflectory, I think, he thought was his best. He talked about the main title from Ephemera. Pepper once mentioned to me that he thought it was underrated, that people didn’t see that the structure was something like Coltrane’s “Giant Steps.” He was very proud of that composition.

In 1982 I was in the U.S. and I showed up at this spot in New York City. Pepper played there with Jimmy Cobb and Albert Dailey. They were very unfriendly with Pepper. I went into the club just before the first gig was about to start with a lot of eminent psychoanalysts from New York City. It was not the regular crowd that evening! Pepper played, unexpectedly, “Doctor Deep” and I was quite taken aback. I didn’t know he had composed it. I think there’s a lot of love in that piece. There I really feel that Pepper loved me. I play it very often. It’s a beautiful thing.

About the name “Doctor Deep,” I met Jimmy Rowles many years ago. When he heard that I was a doctor in philosophy he mentioned a medical doctor in California he called “Doctor Deep” that used to cure tired musicians. I mentioned that to Pepper. I said, “Maybe I should frame myself with that name?” Pepper laughed very much. After that he named me “Doctor Deep.” Whenever he called me up he said, “Is ‘Deep’ there? How are you doing, Deep?” “Deep” was something that caught him.

When Pepper was in the Army, Charlie Parker sent him a telegram saying that his mother had passed away so he must come home for the funeral. It was, of course, a lie. Pepper was supposed to show up and play with Charlie Parker in Saint Louis. When he came there, there was no Charlie Parker. He told me that story very often, especially when he was drunk. He was very proud of that invitation.

It’s strange: Pepper didn’t have a lot of self-esteem. He often named important jazz musicians he had played with and so on. He had played with that one, he had talked with that one. It was almost like a fan. As a clinician I realize that, when he did that, he had no high regard of himself. Yes, he was very uncertain sometimes. He had his funky spells now and then.

I think he never was satisfied with his own playing. We often sat up in the night talking about how to improve. That was something Pepper came back to again and again: “You must improve, you must improve and get better.”

Pepper had no regard for the avant garde. He didn’t like late Coltrane. He resented that kind of music. In a way, his heart was in the Duke Ellington Orchestra, with Harry Carney. Harry Carney meant a lot to him. He mentioned him very often. He thought Cecil Payne was a very good baritone player. He didn’t like Nick Brignola. He was very much dissatisfied with that record Baritone Madness.

One of the last times Pepper was in Sweden with Thad Jones-Mel Lewis I gave him a record, Don Byas Live at the Old Montmartre. I don’t know why. It was a present. He wrote me back very soon after coming back to the U.S. and said what a fantastic record it was. That record really got him excited. It was something he found much joy in. Then I understood that Byas always was very friendly with him and reacted like he had met a long-lost friend when they met. Pepper thought that it was a two-way influence, a confluence, between Byas and himself, and I think there’s something in it. He admired Don Byas very much. We played Don in my apartment and we often talked about Byas. I taped everything I had and sent it to Pepper. I think he admired Byas because he too was never satisfied to be caught or fenced in a certain style. He always improved and developed. And then, I think, Pepper admired his enormous drinking capacity. I’ve seen Byas drink and that’s something out of the ordinary. Ben Webster he liked too, but he had a brotherhood thing with Don Byas. They build up their solos in a very similar way.

To the end Pepper sent me tapes of himself with highlights from his recordings: from Montreal, Holland, and so on, which I’m very proud of. Pepper was maybe the closest friend I ever had. We were not alike but something got us together. I’m awfully sorry that he and Claudette had a bad time those last years. I don’t think one can blame anyone. I think the relationship just broke. Of course Pepper had his “sides.” He was sometimes drinking too much and I think he could be a bit nasty. He was never with me. When we drank together we had a lot of fun. It was never base drunkenness in a bad way. We talked to each other, into the fog. I heard a lot of things then. We always kept in line with intellectual conversation but sometimes you could feel that he was very close to losing control. He was so controlled, otherwise, when he was sober. An introvert.

He has given me many good things. I got interested in art and literature thanks to him, the kind of literature I never knew of. He introduced me to artists, painters and so on that I never knew of, so I’m very grateful to him for that too. I think he is very much underrated. I think he suffered a lot from that. He knew that he was number one on his instrument but he had no “elbows.” He wasn’t angry enough, aggressive enough to be in the “front line.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)